BBS volunteer Jim Blakelock shares how he got into birding and became involved in an annual North American Breeding Bird Survey route with his friend and avid songbird watcher Sheldon McGregor.

“It was embarrassment that got me into bird watching. After University I spent a number of years working at construction and factory jobs. One of these jobs was at a house with a fruit tree in the back yard. It was fall, a warm day when a flock of songbirds descended on the tree, started to gorge themselves on the fruit. They promptly got ‘high’ on the fermented fruit, and started falling from the branches and staggering about the lawn.”

“The carpenters asked me, “So college boy, what are those birds?” I had no idea. My high priced education drew a blank and then and there I resolved not to get caught short again. It turned out they were Cedar Waxwings and I went on to be able to identify most common birds but was certainly not a crack identifier.”

Jim met Sheldon McGregor in 1976, when he was a student in his homeroom grade 7 class. On the weekends Jim would take students to a local marsh to bird watch.

“More often than not it was just Sheldon and me. In June, the kids restless with the approach of the summer holidays would whine to go outside and play baseball. “Sure,” I told them. “If a Kirtland’s Warbler lands in that tree outside the window.”’

“This caused great anticipation. Baseball was surely about to begin. Except for Sheldon smiling in his quizzical way saying “Don’t go for it guys. This is not a good deal.” Of course Sheldon knew that there were only about 200 pairs of Kirtland’s Warblers in the world and the odds of seeing that particular songbird outside our classroom window were nil. “

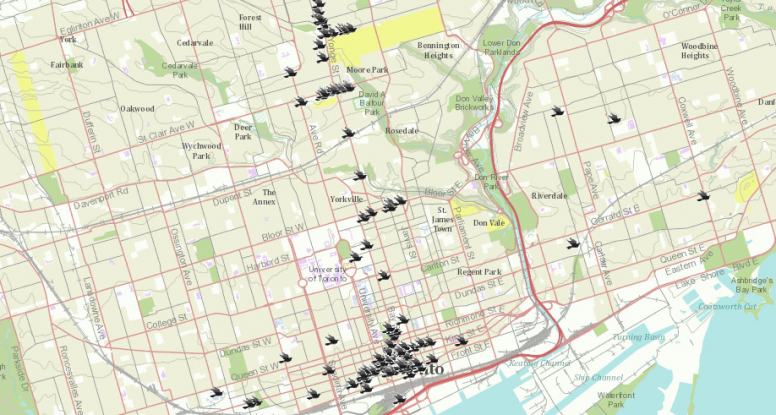

Around 1990 Sheldon asked Jim if he would like to help him with the annual bird population census, the Breeding Bird Survey, and they have been doing it together ever since. They have a route in rural Ontario. Jim records, Sheldon watches and listens. They do this for 3 minutes every half-mile (800 m) a total of 50 times beginning at 5:02 am, ending after 10 am.

In between they catch up on each other’s lives, children, careers, and of course, the birds. Jim is adamant that Sheldon teaches him much more than he ever taught him: the voice of the alder flycatcher or the call of the flicker that really may be a pileated woodpecker. Each of the 50 stops has its own attraction.

One of his favourites is a quiet spot. The trees are thick, leaning over the road tunnel-like. The forest floor is damp and flooded. “It’s here every stop for the past 30 years, that we have heard the Northern Waterthrush calling sharply without fail. It’s reassuring but worrisome at the same time; one wonders will we hear it next year?

Of course a day will come when one, or both of them will not be doing the count. Jim has been retired from teaching for 9 years now. On his retirement Sheldon gave him a lovely pen and ink drawing of a bird – a Kirtland’s warbler.

The Kirtland’s warbler is a bird that is so rare that the Breeding Bird Survey does not have any accurate population data on the species. It is believed that due to conservation efforts there may now be about 5000 in Michigan.

As they head out to do their count this year, Jim and Sheldon hope this is the year when they will actually get to see one.