Çağan Şekercioğlu, a wildlife biologist and activist concerned with saving the wetlands in his native Turkey, has won his country’s highest science prize for his work in conservation. Çağan is also an ardent bird lover and photographer who will be featured in our documentary SongbirdSOS.

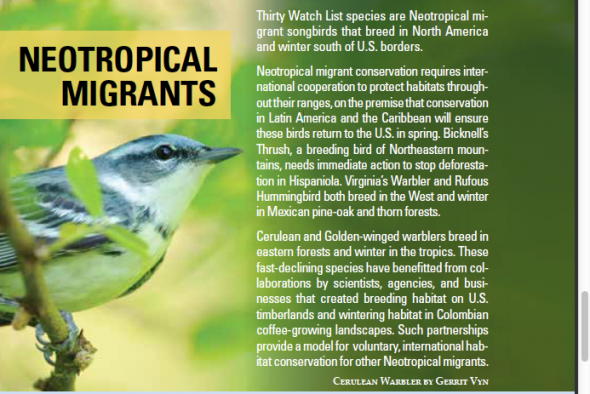

We filmed with Çağan at the Aras Valley Bird Paradise, a conservation site in Eastern Turkey. The region is a globally important wetland. “It’s an oasis,” said Çağan. “These birds are migrating from as far away as South Africa, 4000 kilometers away, on these very long, difficult journeys. This is an important stop-over place where they can rest, feed, breed and some actually winter here too.”

Şekercioğlu’s team of volunteers have recorded 247 bird species at Aras Valley so far and the numbers continue to climb as they study the region further.

Çağan said he was invited to apply for the award last year after he met with Turkish president Abdullah Gül to present him a petition to save the Aras River wetlands from a proposed dam. There are plans in the works for an enormous dam that could destroy the natural wetland, compromising important bird and wildlife habitat. “Turkey now ranks 121st out of 132 countries worldwide in biodiversity and habitat,” said Çağan. “The conservation situation in Turkey is becoming worse as environmental laws are being dismantled and literally being thrown aside.”

In spite of this challenging climate, Çağan and his team have been able to accomplish a lot, including successfully campaigning the government to declare Eastern Turkey’s first protected wetland, building the country’s first bird nesting island and instituting the first wildlife corridor.

“If my receiving this award can convince the government to not destroy the wetlands where I do my scientific research, the cycle will be complete,” said Çağan.

Şekercioğlu was among five top international researchers selected for the 2014 awards by TUBITAK, the Scientific and Technical Research Council of Turkey. The award celebrates scientists from Turkey that work abroad (Çağan is also a professor at the University of Utah in the USA). He is the first ecologist, ornithologist and conservation biologist to receive the prestigious award.

Çağan Şekercioğlu’s is the founder and director of the environmental organization KuzeyDoga http://www.kuzeydoga.org/ KozeyDoga conducts long-term ecological research, biodiversity monitoring, community-based conservation and wetland restoration. It also promotes village-based bio-cultural tourism to provide financial incentives to local communities to support biodiversity and landscape conservation in Turkey.